In the Bronze Age, the definition of Hero was very different. The

raiding and the stealing women and the warlording, the pirating. It's

something we've touched on quite a bit on the blog in relation to

Pirithous, particularly. But what about Theseus?

At a later age, Theseus was known both for his kindness to women and his

kindness to slaves and the weak, and I've always felt that Theseus'

myths reveal a great contradiction, even inside his own character,

between what was considered heroic in that time period, and how he

behaved -- for example, his abandonment of Ariadne (while perfectly in

line with heroics of the time) doesn't really jive with his creation of

this feast day to honor the women who lent him her cow in order to tame

the bull at Marathon, and the way he continued to honor her in

perpetuity for her help. Would a man who repays that small help from a

woman so grandly repay Ariadne for HER sacrifice and aid so cruelly as

to abandon her without a moment's thought or regret?

I have a hard time reconciling it, personally, which is why I think

keeping the gods in these myths is so important. Without the hands of

the gods manipulating and abusing these heroes, their actions make so

much less sense. Their *characters* make so much less sense.

Yes, Theseus must prove himself, and there are plenty of ways in which

he does so in a way that is related more to self-sacrifice than

self-service. Yes, his primary motivation is to preserve the memory of

his name, to build reputation and be known. But Theseus takes up this

call differently than, say, Heracles. He doesn't just go about looting

and pirating for the sake of looting and pirating. He clears the Isthmus

road of the monstrous villains who lurk upon it, making the way safe

for travelers and trade. He goes to Crete to liberate Athens. He even

gives up some small measure of his power as king to allow for his people

to have a say in their governance, if the Theseus as the Father of

Democracy is to be believed. These are the things Theseus is known for,

the way in which his name is remembered.

No matter what the meaning of hero was in the bronze age (or the Homeric

age), these are all still remarkable achievements, and it opens the

door to allow for a slightly different KIND of hero, for that period.

(With Pirithous at his side to remind us of all the less savory meanings

of the word Hero, of course. The braggarting, the swagger, the

arrogance and righteous belief that anything you had the strength to

take was yours to make off with, the glory without consideration for

anyone else, at the expense of everyone else.) Theseus would NEVER have

sat out during the Trojan war, and let his fellow soldiers die just

because his prize was stolen from him, and the slight to his honor as a

result. But then again, Theseus would probably not have served under

Agamemnon to begin with. (Would Agamemnon even have been able to hold so

much influence, to be the warlord he was, if Theseus had still been

King of Athens?)

But is it any wonder that the Athenians would latch on to these virtues?

That Theseus would possess the seeds for them, when he is THEIR hero,

particularly. The answer to Heracles. I mean, we can sit here and debate

the chicken or the egg -- which came first, and what does it mean for

the actuality and historicity of Theseus, King of Athens. Did the

Athenians read all of these virtues back into their hypothetical

founding father, or did he possess these virtues to begin with, and

those ideals carried forward through the ages, a lasting mark of his

reign?

For myself, I want to believe the latter. I want to believe that Athens

developed as it did (in contrast to Sparta and the other city-states)

BECAUSE there was some seed planted by those early kings. That Theseus

came first, and the rest followed.

Long before she ran away with Paris to Troy, Helen of Sparta was haunted

by nightmares of a burning city under siege. These dreams foretold

impending war—a war that only Helen has the power to avert. To do so,

she must defy her family and betray her betrothed by fleeing the palace

in the dead of night. In need of protection, she finds shelter and

comfort in the arms of Theseus, son of Poseidon. With Theseus at her

side, she believes she can escape her destiny. But at every turn, new

dangers—violence, betrayal, extortion, threat of war—thwart Helen’s

plans and bar her path. Still, she refuses to bend to the will of the

gods.

A new take on an ancient myth, Helen of Sparta is the story of one woman determined to decide her own fate.

*

*  *

*

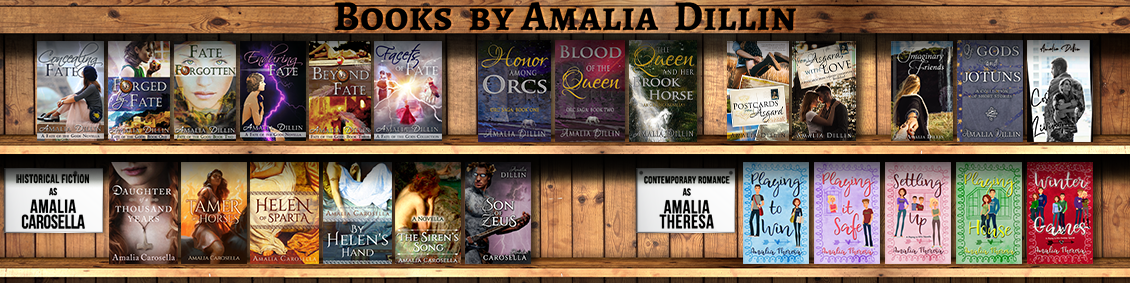

Buy Now:

Amazon | Barnes&Noble

*

*  *

*