Over on Gary Corby's blog, there have been some really good posts about religion in Classical Greece, and it's gotten me thinking again about where we draw the line between mythology and fiction, a discussion I've been wanting to begin here for a while.

The word Myth has some serious connotations of religious aspects, while at the same time carrying with it the implication of fiction. When you take a minute to consider the things we call myth, and consider to be mythology, you generally end up looking at religious stories of now defunct, or practically dead religions. Religions which, for one reason or another, are no longer recognized or state-sanctioned, though at one point they may have dominated in a particular region or area of the world. Myth is a politically correct way of calling the stories of an entire people, an entire faith, fiction. Myth is what we say when we're talking about gods, heroes, and faith traditions, that we have decided as a culture, as a race, as a country, as an individual, are invalid and utter hogwash. The things we don't believe in, but somebody else does.

Generally speaking, you don't see people going around accusing The Bible of being mythology-- although the reality of the situation is that it isn't any better or any worse than most of the other collections of stories and beliefs of religions that didn't survive the spread of Christianity. I guess in some ways the word Myth can be compared to the term Barbarian. Originally, Romans and Greeks used the term Barbarian to describe anything Other and outside of themselves. The Germanic tribes, for instance, were considered barbarians. Others. A group of people culturally different from themselves. Myth is what we call the beliefs and stories of those others in a parallel way. Our personal beliefs are not Myth, but Truth. Everyone else on the other hand... That's another story.

But here's the tricky part. Somewhere, somewhen, and to someone, those things we call myths were Truth. History. Fact. They were part of reality, woven into culture and religion and daily life. They were the real thing (whether they actually happened or not). They were The Bible of another race, another culture, another country, another person. So what exactly is the process which results in turning those Truths, yes, with a capital T, into Fiction? And, can it be argued that Fiction itself can become myth?

When we reinterpret and reinvent the myths of the past, are we giving them new life? Are we adding to the library and depth of the story we toy with? If, as we think we know now, those myths are just fiction, just stories, then what makes the fiction we write with them now, those reinterpretations and reinventions, any less valid? If Thor never did walk the earth, is my modern interpretation of him, my book in which he makes an appearance just as much part of the "true" story of his mythology as what's written in the Sagas?

Three thousand years from now, will the historians look back at my work of fiction involving the Norse Gods, and shelve it beside Snorri's Prose Edda? Why not? If we consider Ovid to have imparted source material of Myth to augment the stories of Homer and oral tradition, if we consider Euripides plays to be documents which chronical mythical events, then is a modern novel dealing with those same stories, those same characters, those same gods, not also part of the myth? And if so, then is it really Fiction anymore? Or has it been turned into something else? Something more?

On the other hand, if those Myths are Truth, are actuality, are History--maybe we should rethink classifying them as Mythology, and grant them some kind of greater respect. And, if we're going to allow that some part of a particular myth might be true, or some part of a particular set of religious stories is true, how do we judge with certainty that the rest doesn't bear that same kernal of truth also? And maybe, if we want our truth, our personal Bibles, to be treated with respect, we should stop and think before we dismiss any other story born of faith as Myth.

One final question: if people anywhere are still worshipping a god or gods, can we still call those traditions and stories surrounding that worship Mythology?

Think about it. Talk about it. Ask questions. Ask the hard questions and don't be afraid of the answers.

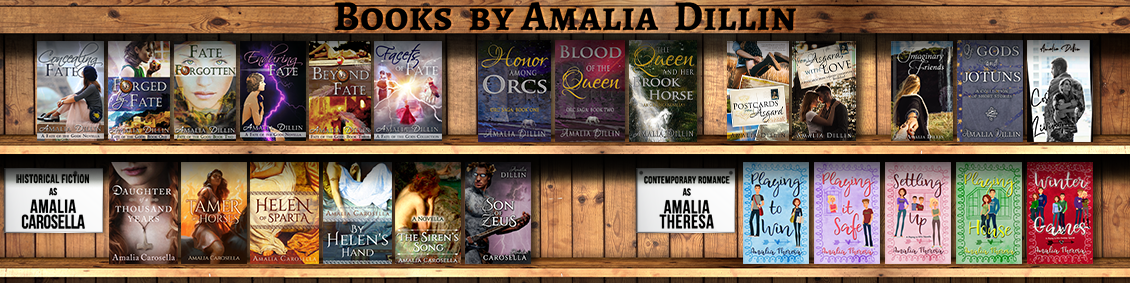

And don't forget to subscribe to THE AMALIAD, to stay up to date on Authors!me. Or become a Patron of my work over on Patreon!

Friday, November 13, 2009

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

I love this post. Love it! I've gotten into a few discussions about this very topic, whether Judaism, Christianity, Islam, etc. will one day be looked upon as intriguing myths by later cultures. But for some reason people get all up in arms about that very idea.

ReplyDeleteHowever, just as you pointed out, those old myths were the Bible of the cultures that believed in them. The Greeks, Egyptians, Romans, and all those other ancient civilizations took their gods just as seriously as people today take Jesus, Moses, and Mohammed.

I've tried to make that apparent in writing Egyptian fiction, but without getting into the gods themselves. I guess that's part of writing to a modern audience and also part of my personal beliefs.

Thanks for the thought-provoking post!

I'd argue that it won't just be Judaism and Christianity and Islam that are going to be look back on as myth, but also our favorite modern heroes. Characters like Superman, and Wonder Woman, Marvel's Thor, The Hulk. People are going to be digging up plastic Superhero action figures forever--and what's to prevent them from seeing those reinterpretations of old myth as part of the evolution of the myths themselves for a modern world?

ReplyDeleteI'm glad you liked this post! These are the kind of questions that playing with the gods in fiction make me ask-- the kind of questions I want the people who are reading my stuff to ask! I'd love to allow people to have the discussion without getting up in arms, and making it personal.

Sherlock Holmes. People thousands of years from now will be writing erudite academic articles pondering whether Sherlock Holmes was a real person.

ReplyDeleteSame goes for whether Lennon and McCartney were one person, or a collection of composers whose songs were written over hundreds of years.

Thanks for the link Amalia!

Exactly! Why not? I mean, don't we do that with Homer? Who was he, did he actually exist, was he a single person or multiple people? Did the Trojan War happen? Who was actually there? For that matter, we argue some of the same questions about Shakespeare, and he wasn't even close to as long ago.

ReplyDeleteAnd you're welcome!

Myth.

ReplyDeleteIn our modern culture, with our Newtonian view of the world, Myth doesn't make sense anymore.

We have "cause and effect", "reproducible results", and peer-reviewed journals to deliver us the Truth. But it's a narrow, starved, desiccated Truth. We focus on objects - that which is separate from the observer - and try to establish "objective truths". We do this first in physics and science, but the fact is, throughout history, we have applied our "physics" mindset to our culture and our philosophy. And to our religion.

The problem is that Myth doesn't describe "objects" - historical artifacts, events, places, or people. Myth describes processes. Archetypal ebbs and flows; relationships between forces that are themselves built from relationships between forces.

And that's the nature of the universe as we now understand it. There are no billiard balls, only collections of intentions flowing through space-time. It will take a long time for the full impact of Einsteinian-Relativistic physics to make it into all the nooks and crannies of our psyche, because the Newtonian view worked so well in helping us to dominate the planet. But it's happening. Slowly, inexorably, and necessarily. It can't be stopped.

What does this little discourse have to do with my Myth vs. your Religion?

Simply this: Nobody interpreted the Bible literally before the Renaissance. It was Myth just like any other.

The irony is that a thing like "Creationism" is an outgrowth of literalism, which is an outgrowth of the Newtonian world-view and the scientific method.

Fundamentalism will die a long and disruptive death. But it will die.

Myth is poised for a comeback.

I disagree that Myth doesn't describe objects. The easiest example of a myth describing an historical event is the Trojan War-- and it describes the people within it, too. The myths surrounding that historical event also describe the other things you suggest--relationships of forces and processes, but at its heart it is still the record of a war that left the people who were engaged by it in ruins. Science proved it.

ReplyDeleteBut this is the challenge: If we accept the Trojan War and the myths around it as something that HAPPENED, how can we then turn around and discount the other stories as things that DIDN'T happen? Biblical, Classical, Norse, Hindu, what-have-you. We do it, with science. There's no proof. And stories and myth alone don't count as proof, apparently, even though we've already used them as evidence.

Science is our substitute for faith. It gives us great comfort to believe we're in control somehow, or able to at least figure out the rules and how to manipulate them for our purposes. And you don't have to beg science to forgive you when you do something morally suspect. Science doesn't care if you're a murderer or a virgin queen.

See, the myth of the Trojan War was History to it's people. Believed to be an event that actually took place, referenced later by Herodotus and Thucydides both. Along with a lot of the other myths. These were real things. Real events. Myth is old history we've discarded and said isn't literal ANYMORE, replaced with something new-- in this case, science. That doesn't mean Myth will experience a resurgence, but rather the cycle suggests that the science that becomes outdated (Newtonian physics) will be relegated into Myth as new and better explanations (Einsteinian Relativism, String Theory, Etc) and truths are found.

I'm also not sure that the old testament wasn't taken literally, at least in pieces (like the story of Moses, the Exodus out of Egypt, and Abraham and Isaac) before the Renaissance. That isn't what the tradition of the Jewish faith tells us. Is it possible that Judaism is imposing post-renaissance beliefs over their history? Sure, just like anything else. But the way in which the stories are recorded seems to support a more literal understanding. They're written as historical accounts. And again, there are instances were we can "prove" with science that events happened--perhaps not exactly as recorded, but generally so.

Literal translation of religious stories is not new. Neither is the compulsion to try on new understandings and new beliefs and throw the old ones away. But we have a habit of throwing out the baby with the bathwater, so to speak, when it comes to these things. Adopt a new, popular, faith and burn down the libraries with all the old scripture. Over-correction to appease the new "gods" whether they be beings or something like science. It's easier to just get rid of it all and start again than it is to examine the old stuff, and allow it to exist and help shape the new with the stuff that's proven. Science kind of allows for that shaping. Whenever it takes a myth and proves it happened, it's saving someone's baby from being tossed out. But Science can't explain everything. Science ISN'T explaining everything. We keep trying to make it, but it's not quite happening.

Fundamentalism's desire to purify the water is just going to poison the baby at the bottom and rot the tub. But in the end, it's going to end up another myth that's been discarded over time. That doesn't make it any better or any worse, it just makes it another over-correction. Another narrow response that can't accept truths proven long before its time. But you can't blame them for taking the new god of Science and applying it to their own beliefs as a "proof" in order to legitimize itself. I mean, that's what all the cool kids are doing these days. That's what science is FOR.

Myth is not about the historical event. Myth is about the grand motifs. Sometimes, an historical event is a convenient launch-pad or canvass for the expression, through myth, of a grand motif.

ReplyDeleteThe fact that the Trojan War actually happened has very little to do with the mythological content of the story, and vice-versa.

I'll posit that the strength and longevity of the story is more because of the mythological value than the historical consequences.

N'est-ce pas?

Mmm...

ReplyDeleteMaybe.

But I don't think its so simple to separate the historical from the myth. I think they're a lot more closely entwined than just a platform or a launchpad. However--that supposition of mine is born from my consideration of where all that belief and power and energy went that was poured into these gods. A personal experience of mythology, if you will.