Rehak compared images of seated figures from frescos (Fig12), sealings (Figs 13, 14), rings (Fig 15), and sealstones to the fresco motifs in the megaron, and put forward the startling observation that almost all seated figures of identifiable sex in Aegean art are female.Hm.

|

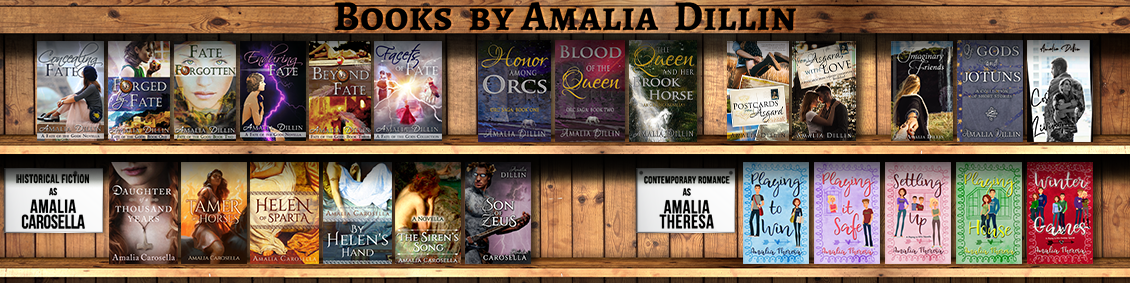

| Mycenaean Ring with a Seated Goddess By Zde (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 ], via Wiki Commons |

Well, for that matter, why couldn't women, as priestesses, have been running the place -- but okay, maybe there isn't a lot of support for that in the linear b tablets, so I can see why no one would want to make that claim.

BUT.

It does, perhaps, put a slightly different spin on the whole "Helen's husband would become King of Sparta" element of the mythology, doesn't it? Because what if Helen weren't just a princess -- what if her role was something greater than that? Something related to the megaron as a ritual and religious space? What if that throne in the megaron was going to be hers?

And not just the myths involving Helen, either, but also the story of Ariadne and Theseus -- Ariadne, the princess of Crete, daughter of Minos. The woman who helped Theseus escape, only to be abandoned on Naxos and made a goddess by Dionysus. Dionysus, who himself may or may not have been related, at that time, to the hearth and the fire and the ritual drinking taking place in the megaron. A priestess Ariadne as the consort of such a god makes an incredible amount of sense.

I'm not sure we'll ever really know one way or the other what the roles of women were in Mycenaean Greece, but theories and discussions like these definitely provide some food for thought.

|

| Available Now! Amazon | B&N | Goodreads |

A new take on an ancient myth, Helen of Sparta is the story of one woman determined to decide her own fate.

*

*  *

*

Buy Now:

Amazon | Barnes&Noble

How Mycenaean women were treated seems to have varied from location to location. From the Linear B archives that exist, women in Pylos were heavily regulated, and the only way a woman could gain status and/or property (and be named in the tablets) was through religion; the only named women in the Pylos archive are priestesses and their female subordinates. In Knossos, it was different. Female workers are individually named (but not, strangely enough, the priestesses or noblewomen), and seem to have had greater freedom than their Pylian counterparts. That may be a holdover from Minoan times.

ReplyDeleteHow things stood in Mycenae or Thebes, their Linear B documents aren't extensive enough to say, and I don't think there's anything from Sparta.

No, there's nothing from Sparta, but I think the fact that Sparta was inherited through Helen in myth is significant, or should be treated so -- even if she's an exception, owing to whatever reason (the belief she was a daughter of Zeus perhaps, or some omen/religious sign), I've yet to uncover another instance in which a woman of that period is the custodian of that much power. It wouldn't surprise me, however, if the treatment and significance of women was highly localized, and their position/status, particularly if it was tied in any way to religion, might well have been subject to whichever local cults were in ascendance in that particular area or region. In later Greece, we see that not every city did things the same way -- the easiest example being the difference between how Sparta treated its women/organized its culture and politics vs Athens, and there's certainly no reason to believe that Bronze Age Greece was really any more homogeneous, palace-center to palace-center. Or at least there's no definitive proof stopping us from allowing for a similar level of variation!

Delete